We know that most roto leagues spend about 31 percent of their total budget on pitching. The reasons for this are debated, and discussed in this recent story. And in Part 2. But if leagues spend $968 on pitching, an average of $81 per team, what is the best way to construct your pitching staff?

Or maybe a better question is whether any one way is better than any other?

The simple answer to the second question is, No! We assign player’s prices based on what we know about them and expect of them. On auction day, we pay them those prices because of our expectations, based on the rules of the game, even though we know certain things:

Expensive pitchers are much, much, much more reliable as a class than cheaper pitchers are.

As a class, pitchers who cost in the teens lose money, but not as much as the class of pitchers who cost less than $10.

The logical conclusion would be to spend on the quality guys, the expensive ones, but there is a problem: If you want to spend $81 on pitching, like the average team in your league, you can afford at best three of the top guys. You just don’t have a big enough budget to acquire more.

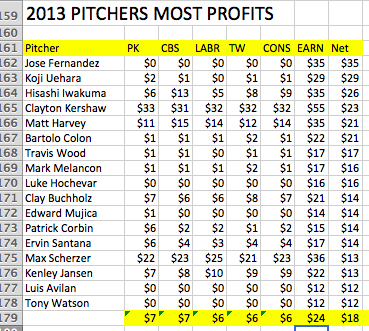

Which is okay, maybe, because while the players who cost less than $10 fail often and spectacularly, half of the end of the year pitching value isn’t even bought in the auction. Take a look (again if you’ve read past posts) at last year’s Most Profitable Pitchers last year):

Most of these guys are in the Less Than $10 class, and 10 of them were a buck or free last year.

It’s important to remember that the $0 and $1 were essentially unwanted. They’re at best a team’s desperate last pick in garbage time, when almost all the money has been spent. Nobody was targeting Bartolo Colon last year, but when the well was almost dry, someone said his name and came up a gusher. And a big winner.

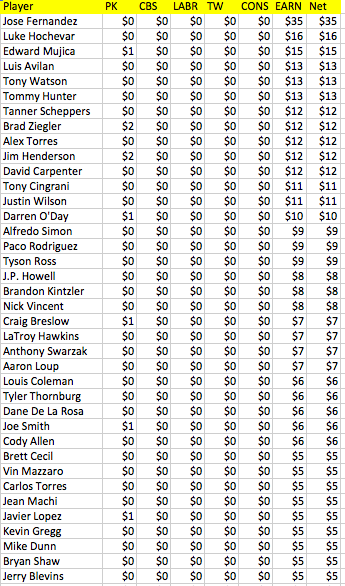

A lot of other pitchers went for $1 last year and failed, which is okay, because pitchers are easily replaceable. Guys like Luis Avilan and Tony Watson, middle relievers without long histories of success or a clear shot at value as a Closer In Waiting, are always available on reserve. As are other pitchers who turn out to have value:

These are the guys who earned $5 and up who were not bought in expert auctions last March.

These are the guys who earned $5 and up who were not bought in expert auctions last March.

Apart from Jose Fernandez, who surprisingly made the rotation out of camp in Miami, and then not surprisingly was one of the best hurlers in the game all season long, this isn’t a list strong with starters.

The fact is that most 5×5 leagues hoover up just about any starting arm they can. There aren’t many valuable starters in waivers, most of these replacement guys are terrible. Or bad. Or middle relievers.

I took a look at what pitchers at each sub-$10 price point did last year. This is very unreliable data. The difference between a $7, $8 and $9 pitcher is negligible, as is the difference between a $1 and a $3 player. Most of the difference can be attributed to when in the draft each was nominated or to other—for the most part—random effects.

I took a look at what pitchers at each sub-$10 price point did last year. This is very unreliable data. The difference between a $7, $8 and $9 pitcher is negligible, as is the difference between a $1 and a $3 player. Most of the difference can be attributed to when in the draft each was nominated or to other—for the most part—random effects.

But we can see that while most of these values lose money, the percentage of pitchers with positive earnings (POS$) is a little higher for the cheapest players. The goal here, remember, isn’t to accrue net value overall, it is to pick off positive earners and churn the losers and turn them into winners, if possible.

So, you might be asking, what’s the strategy?

Well, the correct strategy is to buy the most value you can for the amount of money you have to spend. That’s always the strategy, so you want to buy underpriced guys. But that doesn’t help you construct a solid staff, because in many leagues the top starters are undervalued and you are unable to buy them all because you have a limited budget.

So, you need to maximize the value of your staff in the context of everyone getting bargains (and also getting randomly hit by failures from injury or other unforeseeable circumstances). So, here’re some ideas:

1. Depending on how underpriced top starters are, buy one or two. This should cost you between $20 and $50. This pitcher or these pitchers are your anchor(s). You are looking for reliability and strikeouts. As tempting as it is to pay up for the best guy, be aware that if you go that extra buck or two, other pitchers in the top group will turn out to be bigger bargains. You want any of these guys you can buy for less than your bid price.

2. Buy a closer. Buy the cheapest closer you think has a reliable shot at closing games out all season long. This is tricky business, but ideally you can stay away from Kevin Gregg and his ilk (but pop one of them if they’re very cheap). The important thing to recognize is that there are tiers of closers. High strikeout guys with the job cost $18 to $22. Guys with jobs who do not throw a lot of strikeouts are $15 to $17. Guys with jobs that may be threatened go for $10 to $14. All of these guys will earn much more if they can survive the season as a closer. Their prices varied based on the strikeouts they throw and their perceived reliability. You want a guy in the first tier, but if demand is high (there aren’t many of these guys), drop down into the second group. Again, don’t overpay, and if you’re priced out of that group, Don’t buy a closer. But there are serious good reasons to buy saves in the auction if you get a fair deal.

3a. If you bought one anchor starter you’re going to need to buy some other starters. Look for young guys who have yet to have breakout seasons, who throw strikeouts. Mike Minor last year was a good type to target. He’s earned $9 the previous year and cost $12, at 26 years old. The problem is that Jeremy Hellickson was $12, too, and lost $13 (not a strikeout pitcher). You’re going to have to hit the right guys. The third $12 starter last year was Lance Lynn, a strikeout pitcher whose second-half slump dropped his earnings to $1. Or ignore the guys in the teens because they cost so much, and target a few regulars who are in the $6-$9 range. If they hit, you can earn more profit, and if they miss they will be easier to drop. Then finish with the very cheap starters and closers in waiting.

3b. If you bought two anchors and a closer, you’re in dollar days. Every dollar you spend above $81 puts you at a disadvantage against the other teams in hitting, so your goal is to not go over. It feels bad buying $1 and $2 starters, especially because every one you nominate you think you might want, at least a little, will be bid up beyond your means. But remember that you bought two anchors so that you could prospect among the broken and disrespected, and you need to add as many of those as you can to catch a couple surprises in your big net.

4. Take starting pitchers with your reserve picks, unless there is an obvious hitter who must be taken. With cheap pitchers volume is your friend. So is your ability to reserve or drop them.

5. Take $1 Closers in Waiting. It is tempting to spend $4 or $5 for a strong arm in a backup bullpen role, like Tyler Clippard the last couple of years. He will probably earn the $5 even if he doesn’t get any saves. The problem is that you can acquire guys like Clippard on waivers to replace your failed starters. You can’t count on finding starters with potential on the waiver wire.

6. Look for streaming options, too. Depending on league rules, you may be able to move certain guys up and down each week depending on their matchups. While the obvious splits are usually baked into their price, look for more obscure advantages that others might have missed. For years, lefties in Safeco had a big advantage over righties and road games. Not so much last year, after the fences were changed. A look at last year’s splits inside the splits might point you toward some potential surprises.

7. Look for top minor league prospects who may be just a bit too far away. Sometimes, in the end game, the well runs dry. There are no more starters with even a breath of hope. But there surely are minor leaguers who may lack experience, who have great arms and good control (minor league pitchers with control issues are generally more trouble than they are worth, until they figure out how to control the ball) and who will be promoted if a couple of starters get hurt. That’s upside potential for cheap.

8. You do not want to spend more than $81. In fact, you would like to spend less than $81. You need to have the budget to compete for hitters, who are less volatile and harder to replace via waivers. Especially in power. The less you can get away with spending on pitchers, the better your chances of buying a dominant offense.

9. You might want to spend more than $81, and that might be okay. Chris Liss took issue with No. 8 and he was right. I was trying to make a point about adhering to your goals, because it’s important to keep your eye on what you’re trying to achieve. But it is important to be flexible, too. If great pitchers are going cheap, it’s okay to keep buying them if you’re in a league with trades. Value is value, and if others are letting the pitching categories go in the draft you should find takers afterwards who will offer a fair return in hitters.

Finally, a reminder. This is not a get rich quick gimmick. The key to winning is putting together a solid team by buying bargains, as many as you can find. The goal of this story is to suggest some ways to think about your pitching staff and to offer a consistent approach to constructing it that takes advantage of some of the structural issues with auctioning pitchers.

Good luck!

Pingback: Rotoman’s Agony: What Am I Supposed to Do With Perfection? | Rotoman's Guide

Pingback: Tout Wars: What Happened? | Ask Rotoman